The Federal Reserve is downshifting from overt stimulus to a more normal policy stance. This may not have the effect that some people are expecting, and not along the timeline others are expecting. Knowing the probabilities of the change in policy should help us all plan with confidence for the year ahead.

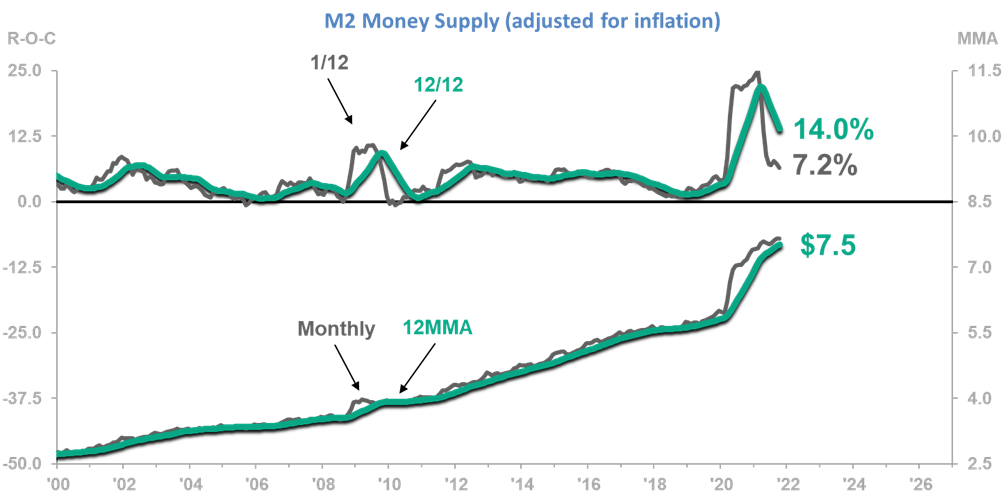

The chart below illustrates the shift from dramatic stimulation. Rate-of-change rise for the M2 Money Supply is depicted on the upper portion of the chart (scaled on the left), and the M2 monthly and annual average data ascent is presented on the lower portion of the chart (scaled on the right); when COVID struck, the rise was sharp for both. All that money made it into people’s hands and stimulated demand beyond what the supply chain could possibly cope with.

The more recent data has the rates-of-change, though still quite elevated, moving toward normal levels, and the monthly data and 12MMA trend leveling off. The trends reflect the Federal Reserve's return to normal growth mode. The questions that arise are:

-

-

- What does this mean for overall economic growth in 2022?

- Will the return to normal hurt retail sales?

- How might this shift impact inflation?

- What does the post-stimulus posture mean for interest rates?

What the policy shift means for overall economic growth

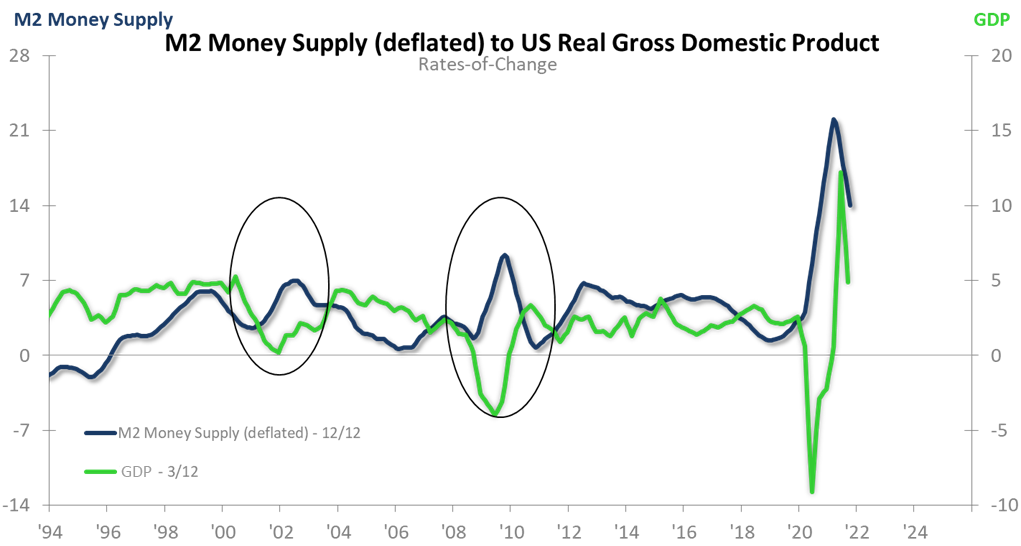

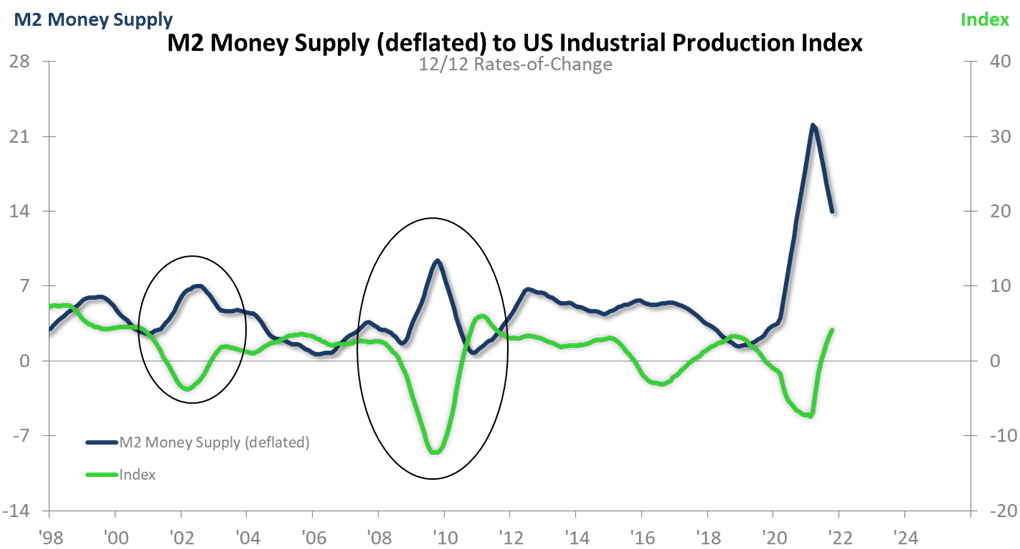

The first chart below compares the M2 12/12 rate-of-change trend to growth in GDP (using the GDP 3/12 rate-of-change). Both series are in inflation-adjusted dollars. The second chart compares M2 to a smaller slice of the overall economy, Total Industrial Production. We circled the post-stimulus period for each of the last two major recessions that received noticeable responses from the Fed: 2001–2002 and 2008–2009.

Note that in both cases the immediate and more dramatic rebound in the growth rates for GDP and Total Industrial Production gave way to more modest growth (as evidenced by decline in the respective rates-of-change). We are expecting the same for 2022. Growth will continue for GDP and Total Industrial Production, albeit at a slower pace than in 2021. Also of note: post-recession recoveries for Nondefense Capital Goods New Orders (excluding aircraft) continued to exhibit strong rising trends in the year following the withdrawal of stimulus.

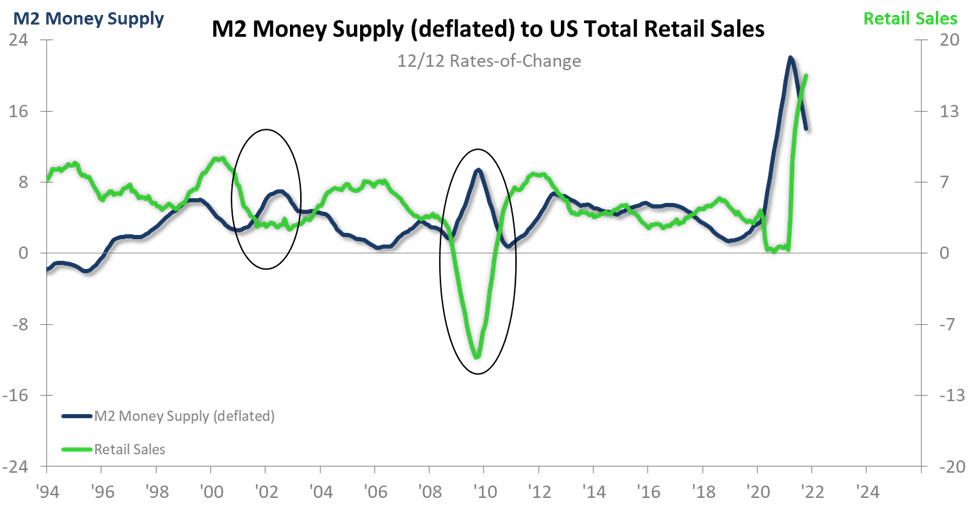

Retail Sales and the removal of M2 stimulus

The chart below shows that the two earlier instances of monetary stimulus withdrawal had no detrimental impact on the growth rate of Retail Sales (nominal dollars), the latter being such a key underpinning of our economy. In both prior instances, Retail Sales returned to a normal-to-slightly elevated rate of growth – strong enough to keep the economy growing. We expect the same will be true in 2022. The issue is arguably made more complex in 2022 owing to rapid wage increases and labor participation/quit rates; however, we think the result will be largely the same in this cycle based on our forecasts for wages and our outlook for disposable personal income per capita, adjusted for inflation (discussed in the December 2021 Executive Summary of the ITR Trends Report™).

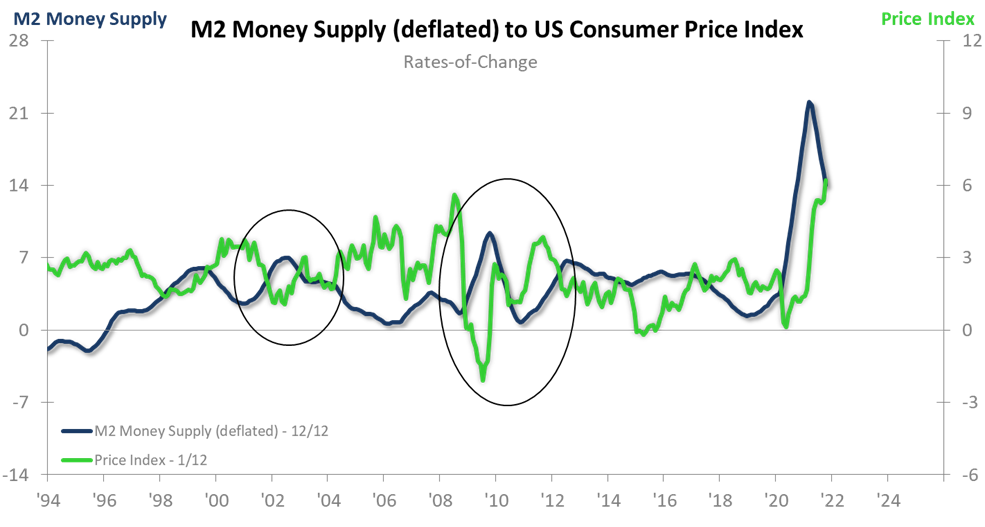

Don’t expect the policy shift to mean inflation will go away

The next chart shows that the downward shift in M2 had a relatively near-term but temporary disinflationary impact on the economy, as measured by the Consumer Price Index 1/12 rate-of-change (CPI). We expect the same will occur in 2022. The current inflation rate will likely peak, with the rate-of-change then moving lower. That means less inflation (i.e., disinflation). However, if you have seen our inflation forecast, you know that we expect the disinflation will be temporary, with a whole new round of high inflation waiting for us in concert with the next business cycle (post mid-2023). The current bout of inflation will temporarily abate, but the beast will be back.

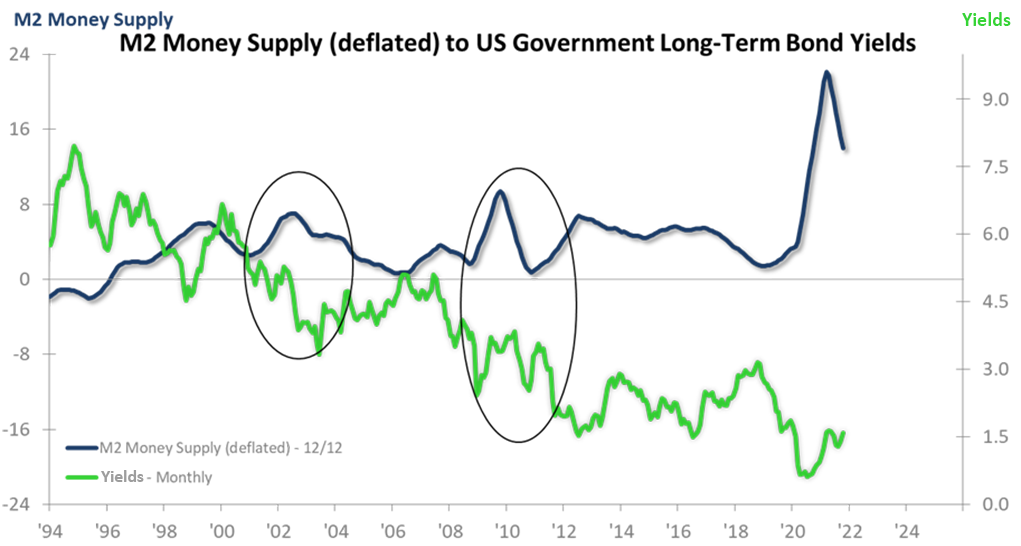

Interest rates will rise, but not enough to harm the economy (for now)

The commonality of the change in long-term interest rates, as represented by US Government 10-Year Bond Yields (monthly data), is that there may be some near-term upside changes in long-term rates, but not enough to be harmful to the economy’s prospects for growth. The more onerous prospects for interest rate rise come in 2024–2025, and the situation is likely to be exacerbated by deficit spending, which will add more and more to our national debt in the future. We are going to experience higher interest rates, but not as soon as some people are thinking. We still have time to take advantage of the current low interest rates and invest in our companies to:

-

-

- Improve efficiencies

- Strengthen our market position

- Move into new markets prior to the potential 2026 recession

Brian Beaulieu

CEO