The US dollar is sliding backward after surging to a more than three-year high in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. The dollar's historical relationship to the US economy suggests this declining trend may continue in 2021.

The US dollar is the world's reserve currency and is considered a safe haven in times of currency uncertainty. This status led to a surge in demand for the greenback back in March and April, as COVID-19 and the associated shutdowns surged across the world, throwing the global economy into chaos. However, the US Dollar Advanced Foreign Economies Nominal Trade Weighted Exchange Rate Index, a weighted index of the dollar's nominal exchange value against currencies of advanced foreign economies, peaked back in April and has retreated since. The Index is now at its lowest level in two and a half years. There are a number of reasons for this decline, and it is difficult to isolate the primary driver at the moment, but for an economist it always helps to start with supply and demand.

On the supply side, US monetary policy has moved in an extraordinarily "easy" direction this year, in an attempt to offset macroeconomic decline brought on by COVID-19 shutdowns. Short-term interest rates have been pushed to zero, and massive amounts of US dollars have been created. The US M2 Money Supply through October was up 24.2% from the same period a year ago, a massive rise that marks the fastest increase in the US Money Supply in more than 60 years. As a fiat currency, the US dollar, like everything else on earth, is subject to supply and demand pressures. When you create more of something, it is worth less, and that is almost certainly part of the story.

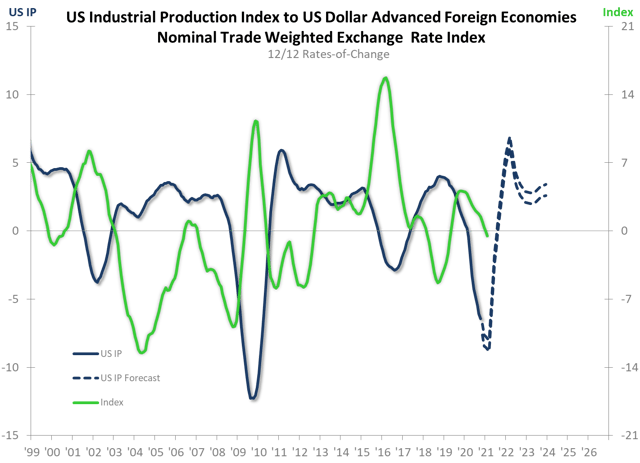

On the demand side, we have observed an interesting dynamic between the US dollar and our domestic economic performance; in recent history, the dollar has typically weakened with a strengthening US economy . This is somewhat at odds with the conventional thinking, that a strong economy should equate to a strong currency and a weak economy to a weak currency. To be clear, the US dollar is, as the world's reserve currency, always relatively strong on a global scale. However, in the 21st century, we have typically seen the greenback weaken as our economy grows stronger, as evidenced in the inverse relationship below:

The comparison shows the cyclical relationship of the US dollar (green line) to the US economy, as represented here by US Industrial Production (blue line). The US dollar strengthened markedly during the last four recessions in the US Industrial Production trend, while the dollar's worst weakening trends typically coincided with periods of overt strength and growth in the US economy, the top of the 2018 business cycle being the most recent example. Now, we see the dollar again weakening, following early 2020 strength, and just as the US economy is about to shift into a higher gear in 2021. We assume that this relationship ties into the demand side of the equation. Periods of US economic distress are almost always periods of global economic distress as well, and during such times we typically see demand rise for more stable currencies, including the US dollar, the Japanese yen, the Swiss franc, and commodities such as gold or silver. As this demand rises, it puts upward pressure on the nominal value of the US dollar.

On the other side of the coin (see what I did there?), when the US economy thrives, the global economy is also typically doing well. Amid these calmer, more stable economic conditions, the global appetite for risk rises, and demand increases for non-US currencies and foreign bonds that offer higher yields. One would also assume a less accommodative slate of monetary policy and slower money supply expansion in the US when economic conditions stabilize and improve.

Assuming the relationship between the US dollar and the US economy remains somewhat consistent with what we have observed during the last 20 years, it appears probable the US dollar will be subjected to general downside pressure during 2021. If we see another surge in shutdowns related to winter COVID-19 cases, we could see a short-term burst of upward pressure on the US dollar as well as financial market volatility, but that would likely be short-lived.

Finally, a weak US dollar is not necessarily a bad thing. Yes, that European vacation will cost you more when the dollar is weak, but no one is taking those these days anyway! Businesses that export out of the US will likely enjoy this weakening trend next year, as it will temporarily bolster their competitive position. US-based companies doing business abroad will see stronger foreign sales on their balance sheets.

Those businesses that import goods and materials will find themselves contending with another margin pressure in 2021, and multinationals doing business in the US will see less positivity in their US-based sales.

If your business has concerns regarding a particular currency, please reach out to us. ITR conducts four-quarter exchange rate forecasts for various currencies around the globe!

Connor Lokar

Senior Forecaster