There are five factors to consider:

- The state of the US economy

- High fuel prices

- The threat of stock market decline

- Higher inflation and therefore interest rates

- A return to normalcy

Special note: Before delving into the economics of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we acknowledge that we cannot begin to speak about the human tragedy, pain, suffering, and reported atrocities committed. At ITR Economics, we must confine ourselves to the economics of events. We believe you count on us for that and for analysis that is unswayed by humanitarian concerns.

Energy Prices

The longer the war in Ukraine goes on, the greater the threat of high oil prices to the US economy. Our analysis indicates that “greater threat” does not mean a downturn in the US is a foregone conclusion if prices stay “too high for too long.” There are other variables at work. The first is energy prices.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is wreaking havoc on energy prices here and abroad. We have previously discussed our concerns for additional recovery in Europe because of those high prices. We now turn our attention to the potential effect of high oil prices, principally via gasoline and diesel fuel pricing, and impacts these high prices may have on the US economy. From a March 9 average high in California ($5.573 for regular to $5.989 for diesel) to the lowest in the country in Kansas ($3.792 to $4.437), extended high pump prices will inhibit some discretionary spending by consumers and bite into profits for some professions (Lyft, limousine companies, airlines, tracking companies). A great deal depends on how quickly fees/charges can be passed through to protect the business, which then leads to consumer price inflation and those associated concerns.

Before dipping into the details, it is advised to keep in mind that we entered this morass in good shape economically:

- After-tax incomes are up (relative to pre-COVID).

- Personal savings are at a post-Great-Recession normal level.

- Jobs are plentiful.

- Debt service levels as a percentage of Disposable Personal Income are low.

- Businesses' liquidity is high.

- Profits are up.

- Money is cheap (in both nominal and real dollar terms).

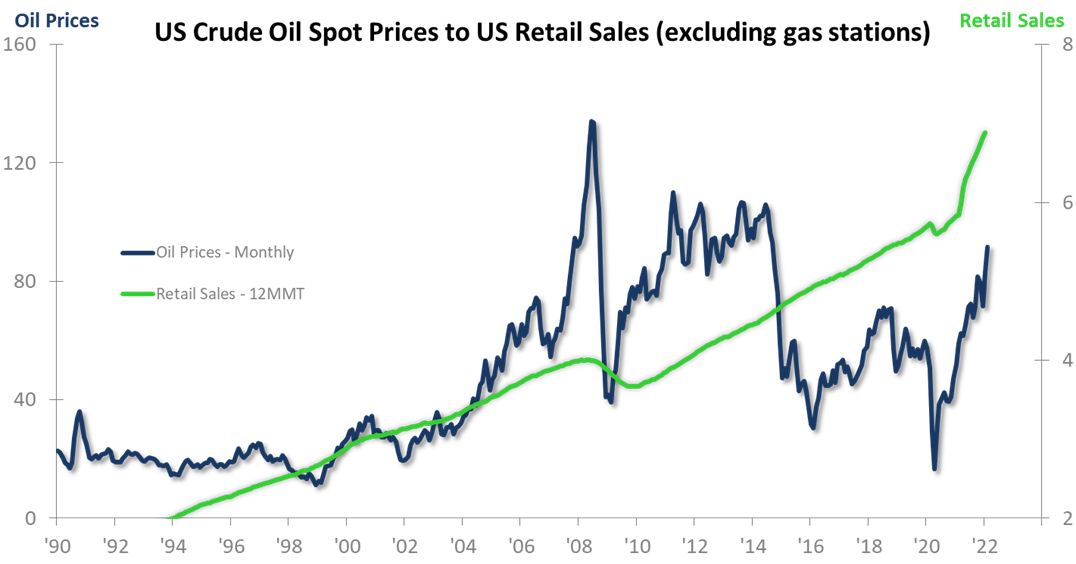

How High Fuel Prices Might Impact Retail Sales

Everyone is talking about it or at least aware of it. Going to the fuel pump is an eyebrow raising occasion. The chart below suggests rising oil prices, which directly drive gasoline and diesel prices higher, do not preclude Retail Sales ascent (we are using retail sales data excluding gas stations so as to avoid a price-inflated view of the trend). The chart shows that the Retail Sales trend continues to rise despite the elevated oil/fuel prices. What is not so evident is that the higher prices can diminish the rate of rise in Retail Sales, although that itself is not a given. We suspect in this case a compounding of factors may play into the result.

One of the exacerbating factors could be weakness in the stock market.

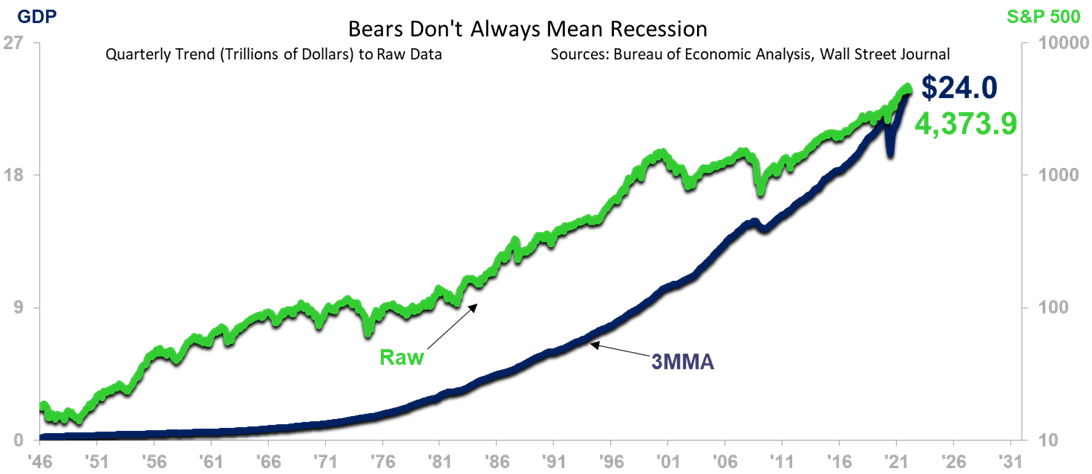

S&P 500 Weakness and GDP

We examined instances of when the S&P 500 slipped into a bear market and when there was a corresponding recession in GDP (adjusted for inflation). A bear market in the S&P 500 for our purposes is any decline of 15% or greater. Note that at the time of this writing, the S&P 500 is in a correction trend (decline but less than 15%, i.e., not a bear market). We continue to expect that the current S&P 500 trend will remain one of correction and not bear market decline; however, even if it were to devolve into a bear market, as some fear, it would not be immediate cause for alarm. We have experienced bear markets without GDP recession in multiple instances: 1966, 1976–78, 1987, 2000–02, and most recently in 2011. It pays to remember that the stock market is not driven by the same fundamentals as the GDP business cycle.

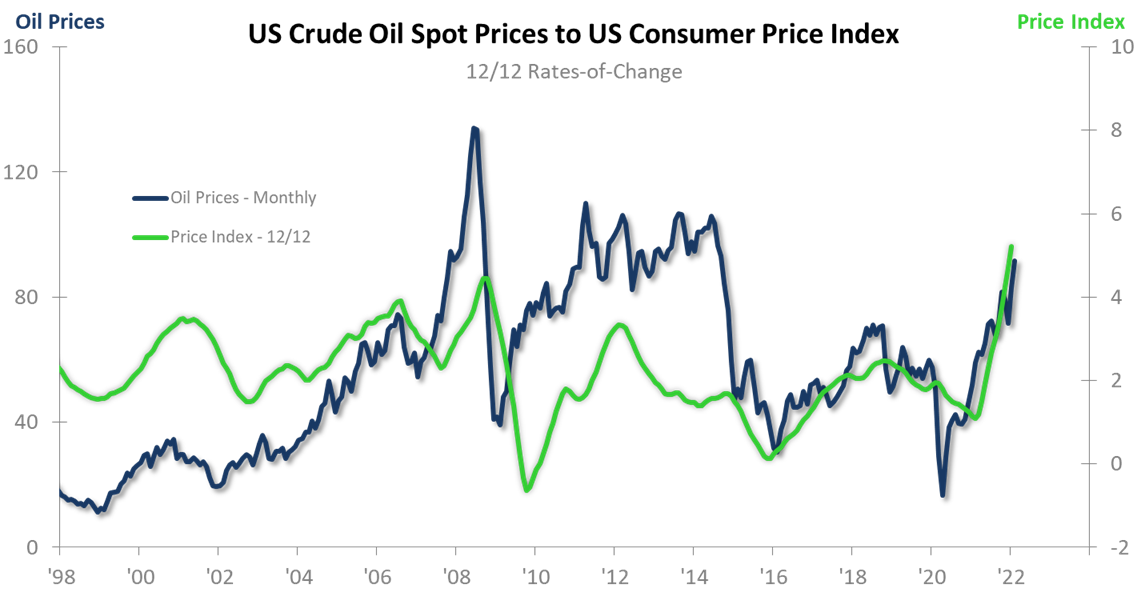

Higher Oil Prices Mean Elevated Inflation

The linkage between oil prices and inflation is more straightforward than the above. Higher oil prices (and therefore gasoline and diesel prices, among other energy prices) will most often lead to higher inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). While inflation will eventually lower the standard of living of the people residing in the economy and will ultimately lead to egregious imbalances, none of that happens in the short term unless the Federal Reserve remains undaunted in its quest to head off current or future inflation. This may be the single greatest threat posed by the higher oil prices. We cannot know what the Federal Reserve will do/say until they meet in a week’s time. There are ample precedents for the Fed not moving against higher oil prices and precedents for when it has. Tempering the magnitude of the potential rate increase in March could be the economic uncertainty imposed by the war, weakness in the stock market, and the bond market signaling that a significant rate hike is not necessary. We hope the Fed reads the trends the same way we are, and they keep themselves confined to a 25-basis-point increase, or 50 basis points at the most. It may come down to what the Fed’s analysis says about the probable duration of the Ukraine war and therefore these very high energy prices.

The CPI and commodity prices in general were in the early stages of shifting from ascent into lower rates of inflation and modest price decline, respectively, before Russia invaded. The war has clearly disrupted the normal course of economics. This is not unusual; indeed, it is normal for a war to do this. What is also normal is that after the war, the economic trends will once again prevail. That means disinflation essentially across the board and lower gasoline, diesel, heating oil, and propane prices (although not necessarily back to pre-war levels).